Today is the first day of Advent 2009. In the wake of the end of the Gathering, I've spent over a year without a liturgical calendar, without the flow and rhythm that characterized my religious life for seven years. As Advent approached this year, I saw it as an opportunity to begin my own liturgical practice again. At the Gathering, we called Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany "Incarnation Season". For Incarnation Seasons past, I read through Walter Wangerin's excellent Preparing for Jesus: Meditations on the coming of Christ, Advent, Christmas, and the Kingdom, and more recently Phylis Tickles' Christmastide: Prayers for Advent through Epiphany from The Divine Hours. both as devotional texts. I find the majority of Christmas devotions to be sentimental in the worst way possible, treating the holiday season with a sentimental reverence akin to Ricky Bobby's "baby Jesus" prayer in Talladega Nights.

But this year, neither Wangerin or Tickle seemed quite right. As I put up our tree last night (yes, I know, many of you don't put your Christmas tree up until Christmas - we put ours up after Gunnar's birthday on November 25, like Americans who do it after Thanksgiving but before the first week of December), I was listening to The Cellist of Sarajevo by Steven Galloway, a book I am teaching next semester. As a spiritually minded man in his early 20s who was often little earthly good, I had largely ignored the events in Sarajevo for theological musings. My ignorance of that conflict forced me to google the siege of Sarajevo as context for my reading. What many of you likely already knew was fresh news to me. I found myself thinking about Trans-Siberian Orchestra's "Christmas Eve/Sarajevo 12/24", a Metallica-esque take on "Carol of the Bells", in an entirely new light.

Add to this the prominence of articles in the news on the end of the world, inspired by the release of the film version of Cormac McCarthy's The Road this weekend. Compound that with my contextualizing of the apocalyptic tension of the Cold War to my students as we study James Cameron's The Abyss; an episode of Boston Legal I'll be teaching to my Analysis and Argument students this week where Nantucket requests the right to build an atomic bomb, not because they really want one, but because no one talks about nuclear threat any more; the relentless dystopia of Battlestar Galactica Season Four; the Edmonton Journal's report on the potential genocide of the world's bat populations, which echoed the H1N1 scare, and got me thinking about the bleak future of Paolo Bacigalupi's calorie-starved world in The Windup Girl. I needed a different meditation for Advent, for Incarnation this year.

Traditionally, Advent is to meditate upon the coming of Christ, either the Nativity of the past, or the Parousia of the future. I chose to go with the latter this year. So this morning over breakfast, I read the preface to Harry O. Maier's Apocalypse Recalled: The Book of Revelation after Christendom. I really enjoyed reading the first chapters of this book, which I picked up at the King's University College bookstore the year before I worked there. I have found I can always count on the King's bookstore for theology that provides me with an edge to grow against. I've never finished the book, but I intend to use it daily this Incarnation season, to temper the apocalyptic tone of my world at the end of 2009.

Maier's basic contention is that Revelation should not be read as "a book to map out an ending to history" (with which I agree completely as a preterist-symbolist), nor only as a "means to comfort churches suffering religious persecution under the Roman Empire" (which is a divergence from the more traditional reading of John's apocalypse), but as a call for Christians to incarnate a "world-ending discipleship." What Maier means by this is more Blood Diamond than it is 2012:

"That is to say, the book [of Revelation] urges Christians to live out an ending to greed and selfishness and to discover a new vision of civic identity centered in the religious particularity of the Christian story, one that interrupts and renounces the forms of violence, greed, and despair that lessen us as human beings...In that sense the book urges an eschatological commitment - a commitment to living endings." (xi, italics mine)

In a terribly complex global community, in a world where the future doesn't look so bright, Christians must do more than just promise that God will someday come to tidy up, or potentially just reduce, reuse, and recycle this broken Creation. We must act in the present to bring the Kingdom, on earth as it is in heaven. Not as a merging of church and state, but in a "counterimperial identity in faithfulness to Jesus Christ." I hesitate even here, knowing how badly such words can be interepreted. I am not advocating for the sign wavers and the political dissidents, for those who lobby for gun-rights and rail against Obama's new health care imperatives. I am advocating for a Christianity that reflects critically "on Christian discipleship in the face of forms of imperial domination, whether they be those of Pax Romana, or of the Pax Americana". And even as I say that, I must remind myself of the freedom I have to publish these words without fear or reprisal. I am not anti-American, or anti-democracy: I am pro-incarnating. Incarnating Jesus into the current society. Tony Campolo has suggested that the ruling society of the day is always Babylon, always in need of critique and careful consideration.

At the very least, I am definitely railing against only comfortably contemplating the Christ child in a sentimental, romanticized fashion, or anticipating the apocalypse with a rabid fervor that echoes the cultic madmen of Lovecraft's Cthulhu mythos. In Maier's words, "an otherworldly reading of John's Apocalypse is a fundamental misreading of Revelation."

"Preoccupied with a call to faithful witness, Revelation offers a portrait of this-worldly discipleship and Christian commitment. If it leaves the future to God, it invites consideration of a present filled with the sounds of faithful testimony to its counterimperial hero, Jesus." (xiii)

If the second advent is a message of hope and not hellfire, one that isn't waiting for the end of time, but the beginning of the Kingdom, then I think more people would echo my prayer today from Revelation 22: Even so, come Lord Jesus.

Sunday, November 29, 2009

Wednesday, November 11, 2009

Poems, on Remembrance Day

Today, the front page of the Edmonton Journal featured an account of one of Canada's "deadliest battles" in the war in Afghanistan. It reminded the readers of how Canadians have not only fought in numerous wars, but continue to be involved in conflicts overseas. Before putting the paper down, I flipped it over, and paused for a moment to read In Flanders' Fields. One must pause to read poetry. We can read journalism quickly, without thought, but poetry, if one stops to read it at all, forces us to slow down through its structure of lines and stanzas. I thought it an interesting commentary on our culture, that the immediate conflict rates the front page, but this piece of poetry is saved for the back. I suppose I ought to be pleased that it warrants a full page, and not simply a side-bar, but I find myself considering the end of William Carlos Williams' Asphodel, where he writes:

My heart rouses

thinking to bring you news

of something

that concerns you

and concerns many men. Look at

what passes for the new.

You will not find it there but in

despised poems.

It is difficult

to get the news from poems

yet men die miserably every day

for lack

of what is found there.

What do I get from the news? I get the latest H1N1 information, or lack thereof. I get misleading headlines and celebrity gossip. I get mostly bad news: murder, gangs, war, a failed economy. Letters to the editor are a revelation of how miserably men die every day for the "lack of what is found there", in the news.

I was more heartened by my reading of In Flanders' Fields than by the article of war in Afghanistan. Perhaps that's only because I teach English. English professors and poets are the only ones who give a damn about poetry any more. It's "despised," as William Carlos Williams says. But "my heart rouses, thinking to bring you news of something that concerns you, and concerns many men." I think it is important to pause for reflection on Remembrance Day: we are encouraged to take two minutes of reflective silence to do so. What will we reflect upon? Some will reflect upon the loss of loved ones, some on the glory of fighting for one's country, others will reflect upon the hope of peace.

This is the purpose of poetry. To allow us to pause, and to reflect. It cannot be quickly digested. It must be mulled, not glossed over. Specifically today, we are encouraged to reflect on the poetry of In Flanders' Fields, which I have copied here for your reflection:

In Flanders Fields

John McCrae

In Flanders Fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Years working with people who seek peace as a first resort has troubled my reflection of the last stanza, both by their devotion to Peace, and by the words of other poets, such as Wilfred Owen. Like John McCrae, Owen also fought in the first world war, but wrote a rather different piece of poetry concerning it. Here is the text, along with the slide I made for teaching this poem in my introductory English classes:

Dulce Et Decorum Est

Wilfred Owen

Bent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of disappointed shells that dropped behind.

GAS! Gas! Quick, boys!-- An ecstasy of fumbling,

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time;

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And floundering like a man in fire or lime.--

Dim, through the misty panes and thick green light

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

In all my dreams, before my helpless sight,

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

If in some smothering dreams you too could pace

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil's sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,--

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori .

While the Latin of this poem was well-known at the time of the Great War, few today are likely to see the ironic twist of Owen's final line, which means, "It is sweet and fitting to die for one's country." The title of this poem, translated from Latin, would simply read, "It is Sweet and Fitting," which contrasts immediately with the opening lines detailing the horror of battle. Perhaps, as a variant reflection this Remembrance Day, you would consider reflecting on Wilfred Owen's thoughts as an alternative to the pastoral poppies. Save the slide and make it your desktop today, and pause for reflection, not once, but several times.

Perhaps you find this suggestion to depart from Flanders Fields misguided, but if you wish to continue to reflect upon the words of John McCrae, I would ask that you leave your poppy pictures behind, and consider this one for your reflection instead, and image of Canadian soldiers at Flander's Fields.

After all, John McCrae might well have been thinking about Longfellow's Aftermath when he penned his words about poppies. In Aftermath, Longfellow presents the reader with what initially seems a nature poem:

Aftermath

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

When the summer fields are mown,

When the birds are fledged and flown,

And the dry leaves strew the path;

With the falling of the snow,

With the cawing of the crow,

Once again the fields we mow

And gather in the aftermath.

Not the sweet, new grass with flowers

Is this harvesting of ours;

Not the upland clover bloom;

But the rowen mixed with weeds,

Tangled tufts from marsh and meads,

Where the poppy drops its seeds

In the silence and the gloom.

Longfellow utilizes carefully chosen words which all convey images of death, of the passing of life. While we consider "aftermath" immediately as a word associated with calamity or death, it was also understood in Longfellow's day as the second cutting after the initial harvest. The image of cut wheat is a powerful one, of new life cut down before it has time to fully grow, a potential metaphor for youths sent to the fields of battle. Students will often cite McCrae's poem to explain why they see the poppy dropping its seeds as an image of death, not recognizing that Longfellow wrote his poem in the nineteenth century, years before In Flanders' Fields. But one has to wonder if McCrae wasn't pondering Longfellow's words, which are simultaneously about a field of harvest, and a field of death.

What is certain, is that McCrae was not picturing a verdant landscape filled with red flowers, but a once-pastoral scene now turned to horror, the image of the Canadian soldiers standing in Flander's Fields. The poppies McCrae suggests are likely the ones which drop their seeds "in the silence and the gloom." We need the poetry of all these writers to properly reflect upon the nature of war. One perspective will not do, or we fail in our remembrance. If we remember only the glory of war, we fail the memory of Wilfred Owen. If we are dismissive of those who fought for the freedom to "wage peace," then we fail the memory of John McCrae, who asked us to "take up our quarrel with the foe." I suppose so long as we see the foe as another human being, we are doomed to honor this day with front pages devoted to the immediate conflict. My hope is that we might some day only have the past to reflect upon, to remember.

Monday, November 09, 2009

It's beginning to look a lot like Christmas...movie season

The year has nearly passed, and of the movies I wanted to see in theatres, I've seen about half. With the Christmas movie season approaching, however, the list of films I'd like to see sooner, rather than later, has grown. While last Christmas was a bit of a deadzone, this year is shaping up to be awesome. Here's my list of films to grab in theater while I'm in Kelowna over the holidays.

Sherlock Holmes: Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law as the world's greatest detective and the admirable Dr. Watson. The trailers display little to no adherence to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's literary corpus: Hollywood neo-Victorian thrillride, I presume?

The Road: I read the book last Christmas, and I'll get to see the movie this Christmas. Viggo Mortensen seems a great choice for the father in this utterly bleak dystopic tale of a future where family is not only all that matters, but all one has left. For all who feel overwhelmed by the sentimentality of North American Christmas, this one's for you.

The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus: I liked the last Terry Gilliam movie Heath Ledger was in, despite all the bad reviews it got, so I can't really see the downside of this phantasmagoric eye-candy, combined with performances by several of my favorite actors. It seems a more appropriate swan-song for the late Ledger to be remembered by than the admirably played but ultimately dark Joker in Dark Knight.

Christmas Carol: This one is going to take a lot of hits from the critics, but I loved Polar Express and Beowulf, so I'm not turned off to Zemeckis' CGI approach to his last few films. I've also heard rumor that the dialogue is very true to Dickens, as is the film's grim tone. Jim Carey has transcended makeup and masks before; I'm looking forward to watching his performance shine through motion-capture too.

Avatar: While I haven't yet forgiven James Cameron for fighting The Last Airbender for the title of this film, the trailers look amazing enough to cover over all wrongs. Plus, it's the first film one of the most brilliant talents in Hollywood has made that didn't involve shooting marine documentaries, so I'm not complaining. It's probably the one I'm most excited about. I don't think James Cameron has made a movie since Pirahna 2: The Spawning I wasn't blown away by.

Twilight Saga: New Moon: I'm man enough to admit when I'm wrong, and I just can't get enough of Stephanie Myer's supernatural hotties and their post-adolescent adventures...

Yeah, right. Hopefully all the Twilight-teens will keep the other theaters clear to see the movies I want to see.

Sherlock Holmes: Robert Downey Jr. and Jude Law as the world's greatest detective and the admirable Dr. Watson. The trailers display little to no adherence to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's literary corpus: Hollywood neo-Victorian thrillride, I presume?

The Road: I read the book last Christmas, and I'll get to see the movie this Christmas. Viggo Mortensen seems a great choice for the father in this utterly bleak dystopic tale of a future where family is not only all that matters, but all one has left. For all who feel overwhelmed by the sentimentality of North American Christmas, this one's for you.

The Imaginarium of Doctor Parnassus: I liked the last Terry Gilliam movie Heath Ledger was in, despite all the bad reviews it got, so I can't really see the downside of this phantasmagoric eye-candy, combined with performances by several of my favorite actors. It seems a more appropriate swan-song for the late Ledger to be remembered by than the admirably played but ultimately dark Joker in Dark Knight.

Christmas Carol: This one is going to take a lot of hits from the critics, but I loved Polar Express and Beowulf, so I'm not turned off to Zemeckis' CGI approach to his last few films. I've also heard rumor that the dialogue is very true to Dickens, as is the film's grim tone. Jim Carey has transcended makeup and masks before; I'm looking forward to watching his performance shine through motion-capture too.

Avatar: While I haven't yet forgiven James Cameron for fighting The Last Airbender for the title of this film, the trailers look amazing enough to cover over all wrongs. Plus, it's the first film one of the most brilliant talents in Hollywood has made that didn't involve shooting marine documentaries, so I'm not complaining. It's probably the one I'm most excited about. I don't think James Cameron has made a movie since Pirahna 2: The Spawning I wasn't blown away by.

Twilight Saga: New Moon: I'm man enough to admit when I'm wrong, and I just can't get enough of Stephanie Myer's supernatural hotties and their post-adolescent adventures...

Yeah, right. Hopefully all the Twilight-teens will keep the other theaters clear to see the movies I want to see.

Saturday, October 31, 2009

I am the Zombie Emperor! Or, Why I got my H1N1 shot

So everyone has been asking me this past week why I bothered to get immunized against H1N1. Is it because I'm a critical thinker and know that despite the fact that several people have died from Hamthrax, no one has died from an immunization? Is it because I'm a responsible parent and I don't want to live my life regretting a flagrant disregard for my children's safety? Or is it because I'm an educator who comes into contact with numerous individuals every day who could make me sick with just about anything?

No.

It's because I heard it's a government conspiracy to turn us into zombies. The way I see it, if that's true, then we're all screwed anyhow, and the sooner I get on the zombie bandwagon, the better off I'll be.

Point one: if I take my whole family, then we can all be zombies. No moment of indecision about whether or not to take a chainsaw to a loved one if you all go undead at the same time. The family that slays together, stays together...and vice versa.

Point two: I would rather be made into a zombie with a needle. It hurts, but not like having a zombie take a chunk out of your bicep, or eviscerating you, or eating you alive. I'm pretty sure those hurt worse than the pin prick.

Point three: If I'm one of the first zombies on the block, then I will spawn more zombies, and will accordingly be a zombie overlord much earlier than the rest of you. I've been told since the second grade that I am a natural leader, and I'm pretty sure the dominant personality traits will carry over into my life as an undead brain-eating shambler. Or maybe I'll be a fast-Zack-Snyder-style zombie. I'm pretty sure if the government is eliminating its tax base by making us undead, we'll be fast ones.

Happy Halloween everyone!

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Josh and Caleb

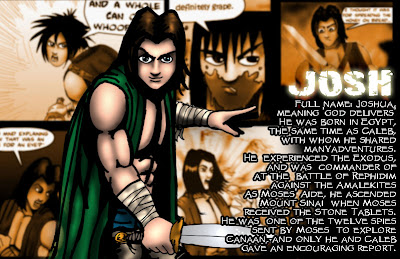

A long time ago, I took a stab at drawing a webcomic called "Josh and Caleb." It was an experiment for me in many ways: as an artist, I was trying to draw in a style I'd never really done before - a mash-up of Disney and Manga; as a graphic designer, coloring and lettering and formatting it all; and as a pastor, playing with the story of the twelve who were sent to spy on the Promised Land. When I took down Gotthammer.com as a website, I had to pull down Josh and Caleb. I need to get these images back up on the Net. Might do it here, might find another venue specifically geared to webcomics. But in the meantime...here's the intro cards to the two main characters.

Monday, September 14, 2009

A People's History of Christianity

In addition to the misuse of apostrophes, I am annoyed by statements to the effect that "religion is responsible for more killings than anything else," or "religious people are nothing but sheep" or other vague, uninformed blanket statements. On the other hand, I find it equally frustrating to hear Protestants talk as though God was letting the Church coast into the depths of heresy for nearly 1600 years before Martin Luther and John Calvin came along and gave Catholicism an enema. Having been part of a "hipper-than-thou" congregation, I've also learned the folly of implying that one has "found the way to do church" like no one ever has before.

For all of these people, I recommend Diana Butler Bass's A People's History of Christianity.

Divided into five parts, the book highlights a number of grassroots moments in the history of the church, showing how Christians of each major period in Church history were trying to make sense of their faith. Each part is further subdivided into a repeating trinity: first, presenting the title "Christianity as..." followed by "A Way of Life," "Spiritual Architecture," "Living Words," "A Quest for Truth," and finally, "Navigation"; second, a meditation on how each period showed devotion to Christ based on their understanding of their faith, and third, how this affected Christian ethics of the time.

Butler-Bass begins by differentiating the history she is telling from other Christian histories by creating a difference between militant Christianity and generative Christianity:

"Whereas militant Christianity triumphs over all, generative Christianity transforms the world through humble service to all. It is not about victory; it is about following Christ in order to seed human community with grace." (11)

As anyone who frequents my blog will know, I dislike unfair polarizations such as spirituality vs. religion, which posits one as good, and the other bad, without being aware that from a sociological perspective, spirituality is religious - a better polemic would be organized religion vs. organic religion, or something like that. So I appreciate that Butler-Bass creates a fair polemic to base her argument upon.

Butler-Bass situates her history as the story behind emergent Christianity, which strikes me as a necessity, given that antagonists of emergent movements have rightly supposed the roots of emergent Christianity to be in medieval Christianity: while this is clearly a negative to the conservative detractors of emergent Christianity, Butler-Bass provides emergent adherents with a history, a story to contradict the perception that emergent churches are doing something solely hip and new. Movements without histories and traditions can find themselves adrift. Butler-Bass provides a basis for the tradition Leonard Sweet called the "anchor" of the church in Aqua Church: "What progressive Christianity needs to understand is that "emerging" Christianity has a story. Their faith is not new; the generative faith of Great Command Christianity is a reemerging tradition that has always been the beating heart of Christian history" (12).

Yet I think A People's History of Christianity is a book for all branches of Christianity, at least those who can stand some real ecumenism, not simply gestures towards it. What occurred to me in my reading was how necessary the reminder of how diverse the church is, and that this diversity is not wrong; an apostate church requires reformation, not rejection. It requires revolution, but not removal. The curse of the Protestant movement is that it has encouraged believers to reject their current church experience, remove themselves from it, and then begin to reform. The blessing of this, if we can find a way to reconciliation (which I am increasingly more cynical of with each passing year) we can exist in the beauty of this diversity.

A People's History chronicles how, over the history of the church, there have been diverse grass roots movements: some break off from the institutional church and start anew, some stay inside and seek to reform from within. We are reminded that there have been numerous forms of Christianity over the past 2000 years, and those movements, those eras, cannot be dismissed or applauded as unilaterally bad or good. In her section on the Middle Ages, Butler-Bass concedes the fact that few contemporary Christians draw analogies with the church of the Middle Ages, stating that it is "fashionable in some circles to deride the medieval church as part of "Christendom," a political arrangement that joined church and state in a hierarchy of power that compromised vital faith." And yet, she notes, there is renewed interest in certain aspects of Medieval Christianity, and while she admits the errors of the day, she also shows the side of medieval Christianity few history texts focus on, and relates the medieval people's need for visual texts to teach them the narrative of their faith. They had stained glass, we have video screens. Admirably, she doesn't reduce this comparison naively, supposing that we're just like the early Christians. Butler-Bass is a serious historian. Her goal is not to encourage nostalgia on the part of her readers, but to show how what is new has a precedent. After all, isn't it encouraging to find that the church has done what we are doing before, and that it spoke to the church in a similar way to how we see it speaking to congregations today?

If you are a student of church history, either amateur or professional, there will likely be familiar content here, but in addition to these well-known moments, such as the Protestant Reformation, there are many surprises: a town in Spain where Judaism, Islam, and Christianity coexisted peacefully; Harry Emerson Fosdick's idea that "faith made evolution make sense" (270); and the historical precedent for how "dispensationalism is not the only version of the Christian apocalyptic" which she sees as "essentially a hopeless vision of a hostile universe" (128). It is a delightfully accessible book which never stoops to dumbing down. It is like sitting in on a great lecture on Church history. If I'm ever at the Cathedral College of the Washington National Cathedral when Diana Butler Bass is speaking, I'm sneaking into a lecture.

Butler-Bass situates her history as the story behind emergent Christianity, which strikes me as a necessity, given that antagonists of emergent movements have rightly supposed the roots of emergent Christianity to be in medieval Christianity: while this is clearly a negative to the conservative detractors of emergent Christianity, Butler-Bass provides emergent adherents with a history, a story to contradict the perception that emergent churches are doing something solely hip and new. Movements without histories and traditions can find themselves adrift. Butler-Bass provides a basis for the tradition Leonard Sweet called the "anchor" of the church in Aqua Church: "What progressive Christianity needs to understand is that "emerging" Christianity has a story. Their faith is not new; the generative faith of Great Command Christianity is a reemerging tradition that has always been the beating heart of Christian history" (12).

Yet I think A People's History of Christianity is a book for all branches of Christianity, at least those who can stand some real ecumenism, not simply gestures towards it. What occurred to me in my reading was how necessary the reminder of how diverse the church is, and that this diversity is not wrong; an apostate church requires reformation, not rejection. It requires revolution, but not removal. The curse of the Protestant movement is that it has encouraged believers to reject their current church experience, remove themselves from it, and then begin to reform. The blessing of this, if we can find a way to reconciliation (which I am increasingly more cynical of with each passing year) we can exist in the beauty of this diversity.

A People's History chronicles how, over the history of the church, there have been diverse grass roots movements: some break off from the institutional church and start anew, some stay inside and seek to reform from within. We are reminded that there have been numerous forms of Christianity over the past 2000 years, and those movements, those eras, cannot be dismissed or applauded as unilaterally bad or good. In her section on the Middle Ages, Butler-Bass concedes the fact that few contemporary Christians draw analogies with the church of the Middle Ages, stating that it is "fashionable in some circles to deride the medieval church as part of "Christendom," a political arrangement that joined church and state in a hierarchy of power that compromised vital faith." And yet, she notes, there is renewed interest in certain aspects of Medieval Christianity, and while she admits the errors of the day, she also shows the side of medieval Christianity few history texts focus on, and relates the medieval people's need for visual texts to teach them the narrative of their faith. They had stained glass, we have video screens. Admirably, she doesn't reduce this comparison naively, supposing that we're just like the early Christians. Butler-Bass is a serious historian. Her goal is not to encourage nostalgia on the part of her readers, but to show how what is new has a precedent. After all, isn't it encouraging to find that the church has done what we are doing before, and that it spoke to the church in a similar way to how we see it speaking to congregations today?

If you are a student of church history, either amateur or professional, there will likely be familiar content here, but in addition to these well-known moments, such as the Protestant Reformation, there are many surprises: a town in Spain where Judaism, Islam, and Christianity coexisted peacefully; Harry Emerson Fosdick's idea that "faith made evolution make sense" (270); and the historical precedent for how "dispensationalism is not the only version of the Christian apocalyptic" which she sees as "essentially a hopeless vision of a hostile universe" (128). It is a delightfully accessible book which never stoops to dumbing down. It is like sitting in on a great lecture on Church history. If I'm ever at the Cathedral College of the Washington National Cathedral when Diana Butler Bass is speaking, I'm sneaking into a lecture.

Saturday, September 05, 2009

Inglourious Basterds

I'm done with rating movies. After a year-and-a-half teaching college literature, I can no longer assess a movie as five stars, or 10/10, or an A+ without giving people the impression I liked or recommend the movie. Likewise, I love some movies that are simply garbage from the perspective of whether or not they're quality. I can assess critical aspects of a film without enjoying it at all, or opine reflectively from a highly objective standpoint, so perhaps I'll just do all these things, and leave ratings for the professional movie critics. Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds is a perfect example of what I'm talking about, and so it serves as a great way to announce I'll no longer be rating films, as well as kick-start my posting at Gotthammer again.

I'm done with rating movies. After a year-and-a-half teaching college literature, I can no longer assess a movie as five stars, or 10/10, or an A+ without giving people the impression I liked or recommend the movie. Likewise, I love some movies that are simply garbage from the perspective of whether or not they're quality. I can assess critical aspects of a film without enjoying it at all, or opine reflectively from a highly objective standpoint, so perhaps I'll just do all these things, and leave ratings for the professional movie critics. Quentin Tarantino's Inglourious Basterds is a perfect example of what I'm talking about, and so it serves as a great way to announce I'll no longer be rating films, as well as kick-start my posting at Gotthammer again.I think Tarantino is very clever, but I have mixed feelings about his style. I like elements, but never the whole product. I love the dialogue, the rejection of standard narrative devices, his quirky casting, and the dense visual pop-culture intertextuality. And yet, despite these parts, the sum has never been a film I would add to my DVD collection. Inglourious Basterds might prove the exception. I say might, because I still haven't decided if I liked it or not, in that subjective way we say we like films when someone asks us what our top ten all time films are.

The fact that I felt compelled to blog about it is surely indicative of Tarantino's ability to, if nothing else, prompt a response. You can't see a Tarantino film and utter a lackluster "feh." You either love it or hate it, in whole or in part.

I loved the performances. I loved the scene in the basement. I loved Shoshanna's story in its entirety. I was impressed by this film on every technical level. And yet, I would be hesitant to say I loved the film. And yet, I don't want to say I disliked Basterds, because I'm nearly 99% sure the reasons I do are part of the subtext of the film. I was disturbed by the violence--I'm inclined to agree with critic Daniel Mendelsohn's assessment that "In Inglourious Basterds, Tarantino indulges this taste for vengeful violence by—well, by turning Jews into Nazis." I would also agree with Tim Brayton, in that "whether Tarantino is a genius or a fool, he does nothing by accident," so I'm not convinced that this reversal is as meaningless as others might. I interpret the violence and reversal as Tony Macklin does: "Inglourious Basterds is a movie that revises history -- it's the Jews who do the marking, it's the Jews who are ruthless, and it's the German high command that is immolated." Nevertheless, with Hostel director Eli Roth on board I can't help but wonder, given Tarantino's filmography, if the gratuitous violence, motivated as it is by revenge, isn't simply gratuitous. I'm undecided. Like Macklin, I agree that one should "try to understand a film as it's meant to be understood. Once you get it, you can apply personal standards and also judge it on its own terms." I'm just not sure what the terms are.

I like the historical revision. After all, I'm writing my PhD on a narrow stripe of counterfactual narrative. I like Basterds from the perspective of alternate history. I like it as a spy movie, or an homage to spaghetti western revenge films. Sadly, I doubt very many viewers will grasp the film as its meant to be understood, or at the very least, as how I'm understanding it. Few are going to ponder how the ending might be a darkly ironic reversal of Auschwitz's gas chambers. Most are just going to talk about Eli Roth as Donny Donowitz, caving in the Nazi prisoner's head with a baseball bat in an over-the-top performance that left a bad taste in my mouth. Stephen Witty mirrors my thoughts on this aspect of the film:

It's these fine sequences that can make you truly regret Tarantino's snarky, in-joke impulses, not to mention his arrogant -- perhaps even dangerous -- lack of concern with the story's moral dimensions. Yes, it's only an action film, and these villains are "only" German soldiers, but the glee with which they're tortured dehumanizes Tarantino's heroes, and possibly us. It's no mistake that horror director Eli Roth is here, in a small role; his scenes play like outtakes from "Hostel."In a year where movie audiences were forced to think very seriously about the complexity of Nazi allegiances in The Reader, I'm worried Basterds is a regression. I wish I could be certain Tarantino meant for us to see ourselves mirrored in the Nazi audience cheering at the graphic deaths onscreen, or for me to be horrified by Donowitz. I was pretty sure that was the point given the last view we have of him manically firing a submachine gun, but the final moments of the film left me wondering. And that's where I still am. Impressed as hell, but still wondering. I think ultimately, I'd agree with Josh Larsen, who said that "Quentin Tarantino has finally made a movie that means something, though I think that’s happened entirely by accident."

Tuesday, June 23, 2009

The end of Gotthammer.com

After nearly a decade, I pulled my hosting of gotthammer.com with domainsatcost.ca down today. The site got some sort of bug, and was coming up with virus blockers with alarming regularity. It's likely no reflection on domainsatcost.ca - they were a great provider. I rarely had problems with my site. But I haven't done anything with the hosted site in well over a year, and everything I do online I do through blogs now. You can still type "gotthammer.com" in - I'm keeping the domain name. That one is MINE! But you'll just come here.

There were a lot of elements of gotthammer.com which people might miss - the images, the webcomic, the reviews. I promise I'll archive those elements here at the blog over the next year. That will allow me to comment on a posted image, and talk about the process I underwent drawing it. As a farewell to the site, I'm posting the original Gotthammer header. This is what you'd have seen if you came by the site for about five years solid. It was my first design, and I still love it like crazy. I don't think I'll keep it up forever, but I'm feeling terribly nostalgic, what with giving up the hosting.

Thanks to everyone who still comes by to see what I'm writing about. Most of my time is spent at the Steampunk Scholar blog these days, simply because I've vowed to focus on my schoolwork until the PhD is finished. So I can't give this blog as much attention. All the same, I'll still be posting, as evidenced by my contributions to the Ooze's Viral Bloggers group - the reviews of Ehrman and McColman's books are part of that. And I'll still be plodding on through Robert Jordan's Wheel of Time series, since apparently the September release will not be the final installment.

Thanks to everyone who still comes by to see what I'm writing about. Most of my time is spent at the Steampunk Scholar blog these days, simply because I've vowed to focus on my schoolwork until the PhD is finished. So I can't give this blog as much attention. All the same, I'll still be posting, as evidenced by my contributions to the Ooze's Viral Bloggers group - the reviews of Ehrman and McColman's books are part of that. And I'll still be plodding on through Robert Jordan's Wheel of Time series, since apparently the September release will not be the final installment.

There were a lot of elements of gotthammer.com which people might miss - the images, the webcomic, the reviews. I promise I'll archive those elements here at the blog over the next year. That will allow me to comment on a posted image, and talk about the process I underwent drawing it. As a farewell to the site, I'm posting the original Gotthammer header. This is what you'd have seen if you came by the site for about five years solid. It was my first design, and I still love it like crazy. I don't think I'll keep it up forever, but I'm feeling terribly nostalgic, what with giving up the hosting.

Thanks to everyone who still comes by to see what I'm writing about. Most of my time is spent at the Steampunk Scholar blog these days, simply because I've vowed to focus on my schoolwork until the PhD is finished. So I can't give this blog as much attention. All the same, I'll still be posting, as evidenced by my contributions to the Ooze's Viral Bloggers group - the reviews of Ehrman and McColman's books are part of that. And I'll still be plodding on through Robert Jordan's Wheel of Time series, since apparently the September release will not be the final installment.

Thanks to everyone who still comes by to see what I'm writing about. Most of my time is spent at the Steampunk Scholar blog these days, simply because I've vowed to focus on my schoolwork until the PhD is finished. So I can't give this blog as much attention. All the same, I'll still be posting, as evidenced by my contributions to the Ooze's Viral Bloggers group - the reviews of Ehrman and McColman's books are part of that. And I'll still be plodding on through Robert Jordan's Wheel of Time series, since apparently the September release will not be the final installment.

Saturday, May 30, 2009

Review: Jesus, Interrupted by Bart D. Ehrman

In the early years of my decade-spanning journey from pastor to academic, I was enrolled in a course at the University of Alberta titled simply, "Jesus." The three textbooks we had assigned to us were: John Dominic Crossan's Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography, which contains the unqualified statement "Jesus was not born of a virgin, not born of David's lineage, not born in Bethlehem, there was no stable, no shepherds, no star, no Magi, no massacre of the infants and no flight into Egypt" (28); Jesus in History, Howard Clark Kee's far more even and fair assessment of the historical Jesus, which I would recommend to any serious student of biblical historical criticism; and Bart D. Ehrman's Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millenium. This trinity of historical critical works, along with Jonathan Z. Smith's Drudgery Divine, nearly shattered my faith in the resurrection. I found myself on Easter Sunday, preaching a sermon on Mary's words, "They have taken my Lord away...and I don't know where they have put him" (John 20:13 NIV). At the end of that particular semester, I could really identify with her.

Nearly 10 years later, I'm wishing it had been Ehrman's latest book on the syllabus. Jesus, Interrupted, while qualifying for one of the most misleading titles of the year, is subtitled Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (and Why We Don't Know About Them), which is the book's truer, albeit less marketable moniker. I was ready to dismiss this book as another one of the bastard children of the Jesus Seminar's legacy, which was exacerbated into a rabid frenzy by Dan Brown's infamous DaVinci Code. One more book about all the stuff the Vatican's been hiding from us? Nevertheless, familiar with Ehrman, and interested in how he was currently rehashing and reusing old material, I began reading.

Jesus, Interrupted was a more than pleasant surprise. I haven't read all of Ehrman's works, although I'm familiar with his reputation. In this book, he lays all his ideological cards out on the table in the first chapters, revealing his own journey to agnosticism, clarifying that historical criticism was not responsible for that agnosticism, and then stating that this book is not an expose of a clerical conspiracy, but rather an attempt to reveal at a lay level what many in the clergy already know, but for ambiguous reasons, are not preaching from the pulpit.

Ehrman's thesis, in a nutshell, as revealed in the subtitle, is that the Bible is full of contradictions, and this is not necessarily a bad thing. Furthermore, as Ehrman discusses in his final chapter, admitting these contradictions does not, of necessity, lead to a loss of faith. This balanced discussion contains no surprises for anyone who's read anything about historical criticism, with Ehrman using what I consider the lynchpin of the argument, the discrepancy in the time of the crucifixion chronicled in the four gospels. He follows this example up by challenging the usual response to the contradictions, which is the assumption that since the facts don't agree, it clearly never happened, or that clearly it doesn't matter, since the point is that Jesus was crucified. The when is immaterial. Instead, Ehrman encourages his reader to ask not "Was Jesus crucified" but also "What does it mean that Jesus was crucified?" And for this, Ehrman continues "little details like the day and the time actually matter" (27).

Whether one agrees with everything Ehrman puts forth in Jesus, Interrupted, his fair treatment of the subject matter cannot be denied. He delineates the difference between devotional and historical approaches, without being derogatory or dismissive of the former. Throughout the book he displays a genuine concern for proper study of the Bible, and an undeniable love of the material he studies, all the while reminding the reader that he is not a professing believer. In chapter seven, "Who Invented Christianity," he allows history to remain a complex process, rather than assuming that it was just the Council of Nicea or the ascension of Constantine which was some sort of ancient tipping point for Christianity to suddenly spring into being.

In the years that followed my "Jesus" course, I had to fight my way through wondering whether accepting historical criticism meant I had to give up on my faith. After all, I was denying everything Josh McDowell had ever written about, and in the late 80s and early 90s, making the statement that McDowell was wrong was a sort of Evangelical heresy. I'm no longer an Evangelical Christian, but I am still firmly rooted in the religious identity of some sort of Christian. Ehrman's Jesus, Interrupted gave me a bit more licence to remain Christian, while still admitting there are some serious textual issues when it comes to the bible. I had learn all this the hard way, and while I'm of Schopenhauer's opinion when it comes to experienced knowledge as superior to read knowledge, I must nevertheless recommend this book. I recommend it for anyone who has some serious questions about the contradictions in the bible, but continue to choose to believe in the truth of the resurrection. I'll end this review with Ehrman's words on the subject, since they're rather powerful. I'm strongly convinced they could have been the closing remarks of my Easter Sunday sermon so many years ago. Maybe they will be for some unpreached Easter Sunday sermon I have yet to give.

Nearly 10 years later, I'm wishing it had been Ehrman's latest book on the syllabus. Jesus, Interrupted, while qualifying for one of the most misleading titles of the year, is subtitled Revealing the Hidden Contradictions in the Bible (and Why We Don't Know About Them), which is the book's truer, albeit less marketable moniker. I was ready to dismiss this book as another one of the bastard children of the Jesus Seminar's legacy, which was exacerbated into a rabid frenzy by Dan Brown's infamous DaVinci Code. One more book about all the stuff the Vatican's been hiding from us? Nevertheless, familiar with Ehrman, and interested in how he was currently rehashing and reusing old material, I began reading.

Jesus, Interrupted was a more than pleasant surprise. I haven't read all of Ehrman's works, although I'm familiar with his reputation. In this book, he lays all his ideological cards out on the table in the first chapters, revealing his own journey to agnosticism, clarifying that historical criticism was not responsible for that agnosticism, and then stating that this book is not an expose of a clerical conspiracy, but rather an attempt to reveal at a lay level what many in the clergy already know, but for ambiguous reasons, are not preaching from the pulpit.

Ehrman's thesis, in a nutshell, as revealed in the subtitle, is that the Bible is full of contradictions, and this is not necessarily a bad thing. Furthermore, as Ehrman discusses in his final chapter, admitting these contradictions does not, of necessity, lead to a loss of faith. This balanced discussion contains no surprises for anyone who's read anything about historical criticism, with Ehrman using what I consider the lynchpin of the argument, the discrepancy in the time of the crucifixion chronicled in the four gospels. He follows this example up by challenging the usual response to the contradictions, which is the assumption that since the facts don't agree, it clearly never happened, or that clearly it doesn't matter, since the point is that Jesus was crucified. The when is immaterial. Instead, Ehrman encourages his reader to ask not "Was Jesus crucified" but also "What does it mean that Jesus was crucified?" And for this, Ehrman continues "little details like the day and the time actually matter" (27).

Whether one agrees with everything Ehrman puts forth in Jesus, Interrupted, his fair treatment of the subject matter cannot be denied. He delineates the difference between devotional and historical approaches, without being derogatory or dismissive of the former. Throughout the book he displays a genuine concern for proper study of the Bible, and an undeniable love of the material he studies, all the while reminding the reader that he is not a professing believer. In chapter seven, "Who Invented Christianity," he allows history to remain a complex process, rather than assuming that it was just the Council of Nicea or the ascension of Constantine which was some sort of ancient tipping point for Christianity to suddenly spring into being.

Christianity as we have come to know it did not, in any event, spring into being overnight. It emerged over a long period of time, through a period of struggles, debates, and conflicts over competing views, doctrines, perspectives, canons, and rules. The ultimate emergence of the Christian religion represents a human invention--in terms of its historical and cultural significance, arguably the greatest invention in the history of Western civilization. (268)One could disagree with Ehrman here, and still conceivably come away without the feeling that their faith has been slandered. Ehrman pays Christianity a very high compliment here, one mirrored in Dinesh D'Souza's What's So Great About Christianity? I am in unequivocal agreement with Ehrman on several points he makes in Jesus, Interrupted, and while I am guarded about some of his conclusions, my reading of this book felt more like an amicable conversation about the academic study of the bible over coffee or beer than it did an attack on the innerancy of the Word of God. I went away from reading it encouraged, and strengthened in my own faith position. As Ehrman rightly says, "a historical-criticism approach to the Bible does not necessarily lead to agnosticism or atheism. It can in fact lead to a more intelligent and thoughtful faith--certainly more intelligent and thoughtful than an approach to the Bible that overlooks all of the problems that historical critics have discovered over the years" (272).

In the years that followed my "Jesus" course, I had to fight my way through wondering whether accepting historical criticism meant I had to give up on my faith. After all, I was denying everything Josh McDowell had ever written about, and in the late 80s and early 90s, making the statement that McDowell was wrong was a sort of Evangelical heresy. I'm no longer an Evangelical Christian, but I am still firmly rooted in the religious identity of some sort of Christian. Ehrman's Jesus, Interrupted gave me a bit more licence to remain Christian, while still admitting there are some serious textual issues when it comes to the bible. I had learn all this the hard way, and while I'm of Schopenhauer's opinion when it comes to experienced knowledge as superior to read knowledge, I must nevertheless recommend this book. I recommend it for anyone who has some serious questions about the contradictions in the bible, but continue to choose to believe in the truth of the resurrection. I'll end this review with Ehrman's words on the subject, since they're rather powerful. I'm strongly convinced they could have been the closing remarks of my Easter Sunday sermon so many years ago. Maybe they will be for some unpreached Easter Sunday sermon I have yet to give.

The resurrection of Jesus was not a historical event that could proved or disproved, since historians are not able, by the nature of their craft, to demonstrate the occurence of a miracle. It was a bold mythical statement about God and the world. This world is not all there is. There is life beyond this world. And the horrible actions of humans, such as crucifying and innocent man, are not the end of the story. Evil does not have the last word; God has the last word. And death is not final. God triumphs over all, including death itself. (276)

Friday, May 22, 2009

Musings on the Terminator and the Matrix

While perusing the reviews for Terminator: Salvation on Rotten Tomatoes, which concur in the assessment that the newest installment in the Terminator franchise is high tech, low heart, I had the thought that the war against the machines was already filmed. It's likely been said elsewhere, but the Matrix Trilogy is certainly the spiritual, if not literal sequel to the storyline the Terminator films set up. There are brilliant cinematic nods to Cameron's films, such as Neo and Trinity's arrival at the skyscraper to free Morpheus. The industrial percussion of the musical score is nearly identical to the music of the Terminator films, and the entry and subsequent slaughter of security guards and policemen mirror each other. The relentless nature of Agent Smith is certainly a nod to the various Terminators.

On a somewhat deeper note, the rise of the machines would certainly have given way to the world the freedom fighters of Zion exist in, or under. Perhaps they exist on a separate time line where John Connor didn't pull things off. At any rate, the last battle of humans against the machines in Matrix Revolutions certainly ends in a way consistent with the progression of Arnold's Terminator from assassin to protector. The final sacrificial moments of Terminator 2 are inverted by Neo, as he makes a sacrificial act to create peace between the machines and the humans, fully realizing the relationship begun by Sarah Connor and the T-100.

While I haven't seen the film yet, my guess is that this is potentially what the new film is missing. Some sense of the transcendent, which is necessary to breathe life into films or stories filled with automatons, be they medieval golems, animated corpses ala Frankenstein (which this new Terminator film apparently shares kinship with), droids, robots, or Terminators. I'll be curious to see if, contrary to the reviewers' opinions, there is indeed a ghost in McG's new machine.

On a somewhat deeper note, the rise of the machines would certainly have given way to the world the freedom fighters of Zion exist in, or under. Perhaps they exist on a separate time line where John Connor didn't pull things off. At any rate, the last battle of humans against the machines in Matrix Revolutions certainly ends in a way consistent with the progression of Arnold's Terminator from assassin to protector. The final sacrificial moments of Terminator 2 are inverted by Neo, as he makes a sacrificial act to create peace between the machines and the humans, fully realizing the relationship begun by Sarah Connor and the T-100.

While I haven't seen the film yet, my guess is that this is potentially what the new film is missing. Some sense of the transcendent, which is necessary to breathe life into films or stories filled with automatons, be they medieval golems, animated corpses ala Frankenstein (which this new Terminator film apparently shares kinship with), droids, robots, or Terminators. I'll be curious to see if, contrary to the reviewers' opinions, there is indeed a ghost in McG's new machine.

Thursday, May 21, 2009

Review of Spirituality by Carl McColman

The full title of Carl McColman's Spirituality includes the subtitle A Postmodern and Interfaith Approach to Cultivating a Relationship With God. The inclusion of "postmodern" is misleading, save as a marker for the inherent uber-ecumenism espoused in the book. The popular view of postmoderns is apparently one where they will accept a more open approach to spirituality. Even the term "interfaith" is somewhat misleading, given how McColman is unabashedly Christian, albeit the sort of Christian conservative denominations would be happy to excise from the fold.

Spirituality is the just the sort of book I enjoyed reading when it was first published in 1997, when I was exploring religious expressions beyond the pale of my Baptist upbringing. McColman seems open enough to other possibilities to be accessible to a wider ideological audience, but still focused enough in his Christian identity so as to not wander overmuch at the religious smorgasbord many writers concerned with "spirituality" like to sample from.

Spirituality is a standard primer for the 21st century spiritual seeker who either has no faith background, has rejected the one they had, or is interested in augmenting the one they adhere to with other possible approaches. The chapter headings and content (Breathing, Wonder, Prayer, Community, to name a few) are standard for this open-approach to faith, mirrored in books such as Anam Cara by John O'Donohue or anything by Thomas Moore. It was the sort of book one found flooding the market in the late 90s as people engaged spirituality with a typical end-of-the-millennium hunger.

There isn't anything earth-shaking or radically new in this second printing of Spirituality. Nevertheless, I have to give kudos to McColman for his balanced treatment of the subject matter. Readers who remember my review of Spencer Burke's A Heretic's Guide to Eternity will recall that I took umbrage with the dichotomy between spirituality and religion. I worried I would be doing the same with McColman, but this was not the case. While McColman concedes that there are many who, for good reasons, distance themselves from religion with the term "spiritual," this is "a bit unfair to religion" (35). Since McColman's thesis is that spirituality is linked to culture, it follows that religious culture is a potential source for spirituality. I like this approach, which in academic circles, would be considered similar to Max Weber's approach to religion. It also includes religious spirituality without making the same sort of polemic Burke seems to in Heretic's Guide, which I have stated many times is an effectively semantic one.

This difference colors the whole of McColman's book. Many times I was worried he was denigrating into relativist fluff, he qualified his statement in a fashion demonstrating his serious and thoughtful approach. I also appreciated his emphasis on community as an essential facet of spirituality. Too many of the self-help approaches to spirituality approach the whole project of faith, to quote N.T. Wright, as a "do-it-yourself project." I recently read a news article about how DIY home improvements most often end up as "bring in the professional to fix my mess" instances. I think a spirituality without community often ends up the same, and I concur with McColman that "A world where spirituality is private is a world where belief in the Sacred is extraordinarily difficult" (33).

I'd recommend Spirituality for people who have recently been hurt by, or become disillusioned with, an institutional form of religion, particularly for Christians who are thinking of giving up entirely. That said, I must make the caveat that anyone who is uncomfortable with more extreme ecumenical positions will probably not connect with McColman. I've always said that "if your faith can't take a walk through a Japanese Tea Garden, it wasn't worth much to begin with," which is to say, if your faith can't endure an open-minded encounter with another faith position, it's not really worth having at all. McColman is comfortable in walking in other gardens, pagodas, mosques, and open fields filled with pagans. I am too, and if that's something you wish you were more of, then you'll probably enjoy and benefit from reading Spirituality.

Spirituality is the just the sort of book I enjoyed reading when it was first published in 1997, when I was exploring religious expressions beyond the pale of my Baptist upbringing. McColman seems open enough to other possibilities to be accessible to a wider ideological audience, but still focused enough in his Christian identity so as to not wander overmuch at the religious smorgasbord many writers concerned with "spirituality" like to sample from.

Spirituality is a standard primer for the 21st century spiritual seeker who either has no faith background, has rejected the one they had, or is interested in augmenting the one they adhere to with other possible approaches. The chapter headings and content (Breathing, Wonder, Prayer, Community, to name a few) are standard for this open-approach to faith, mirrored in books such as Anam Cara by John O'Donohue or anything by Thomas Moore. It was the sort of book one found flooding the market in the late 90s as people engaged spirituality with a typical end-of-the-millennium hunger.

There isn't anything earth-shaking or radically new in this second printing of Spirituality. Nevertheless, I have to give kudos to McColman for his balanced treatment of the subject matter. Readers who remember my review of Spencer Burke's A Heretic's Guide to Eternity will recall that I took umbrage with the dichotomy between spirituality and religion. I worried I would be doing the same with McColman, but this was not the case. While McColman concedes that there are many who, for good reasons, distance themselves from religion with the term "spiritual," this is "a bit unfair to religion" (35). Since McColman's thesis is that spirituality is linked to culture, it follows that religious culture is a potential source for spirituality. I like this approach, which in academic circles, would be considered similar to Max Weber's approach to religion. It also includes religious spirituality without making the same sort of polemic Burke seems to in Heretic's Guide, which I have stated many times is an effectively semantic one.

This difference colors the whole of McColman's book. Many times I was worried he was denigrating into relativist fluff, he qualified his statement in a fashion demonstrating his serious and thoughtful approach. I also appreciated his emphasis on community as an essential facet of spirituality. Too many of the self-help approaches to spirituality approach the whole project of faith, to quote N.T. Wright, as a "do-it-yourself project." I recently read a news article about how DIY home improvements most often end up as "bring in the professional to fix my mess" instances. I think a spirituality without community often ends up the same, and I concur with McColman that "A world where spirituality is private is a world where belief in the Sacred is extraordinarily difficult" (33).

I'd recommend Spirituality for people who have recently been hurt by, or become disillusioned with, an institutional form of religion, particularly for Christians who are thinking of giving up entirely. That said, I must make the caveat that anyone who is uncomfortable with more extreme ecumenical positions will probably not connect with McColman. I've always said that "if your faith can't take a walk through a Japanese Tea Garden, it wasn't worth much to begin with," which is to say, if your faith can't endure an open-minded encounter with another faith position, it's not really worth having at all. McColman is comfortable in walking in other gardens, pagodas, mosques, and open fields filled with pagans. I am too, and if that's something you wish you were more of, then you'll probably enjoy and benefit from reading Spirituality.

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

Final Images - Prodigal Son

Not a regular post, nor will it be necessary to make a habit of this. These images are posted here for my Taylor students' convenience, to look over without having to google them before their final exam, which employs each of these images.

The first set are James Tissot's "The Prodigal Son in Modern Life." Remember - you're comparing these images with the text, not with any extra commentary, theological speculation, or midrash. You must stick to the images, and to the text from Matthew, as found in your Literature textbook.

The first set are James Tissot's "The Prodigal Son in Modern Life." Remember - you're comparing these images with the text, not with any extra commentary, theological speculation, or midrash. You must stick to the images, and to the text from Matthew, as found in your Literature textbook.

Tuesday, March 17, 2009

Why I blog

Richard Ford, in his novel Independence Day, writes:

I was standing in London Drugs today, waiting in line while an old lady dug out her change. A fierce-eyed man behind me muttered about "saving money while you hold up the goddamn line." I imagined replying, "being an asshole for the sake of saving 20 seconds is a far better thing." And then I had a flashback to standing in the aisle of the general store in Fox Creek, which in its entirety was no bigger than the length and width of the checkout area I was standing in.

I remembered being only a year or two older than Gunnar, and standing in that store: looking at the toy section, filled with the sort of nickel and dime junk you find in small town general stores. I recall it being a wonderful place though. I bought Star Wars trading cards there. Comic books. A plastic gorilla who I was convinced was King Kong. A G.I. Joe, the kind that was taller than Barbie, the kind with the kung-fu-grip.

And suddenly, I wanted to be home. I wanted to be where my son is. I want time to move differently. I don't want to be turning 38.

I'm finding it hard to age gracefully, it would seem.

So reading a book about a man in his mid-forties having a coma seems like a cruel and unusual punishment to inflict on oneself. But, like my time, I have no choice in the matter. It's required reading for my Canadian Women's Fiction class. And I need that class to get through my coursework. And I need that coursework to get my PhD.

And somehow, I'm convinced I need that PhD. to get beyond my past. My resume reads, "Only ever really done church work or retail." Which is effectively the most useless resume one can possess. I heard the inside scoop from an HR manager who told me that former pastors are about as unpopular a potential hire as one can find, outside ex-cons.

Yet every day, I ask myself if it is worth the effort. Every day, I wonder if the price is too high. And every day, I am reminded of Winston Churchill saying "if you are going through hell, keep going." Or as Trent Reznor put it, "The Way Out is Through."

Thankfully, Larry's Party doesn't end with the coma. And its central metaphor is the hedge maze, or labyrinth, which is described in the book as "a complex path." If ever I identified with a metaphor, it's this one, at this time.

So why blog? It's 10:53 on Tuesday night and I have another novel to read before class tomorrow. And half of D.H. Lawrence's The Rainbow for Thursday night. Another presentation due next week, along with a short paper on a presentation I did last week.

I blog because my chest hurts. I blog because I find myself occasionally short of breath. I blog to remind myself of the things I'm doing this for. I blog to remember how to write with fucking citations, or pedantic obscurancy, or proper punctuation or grammar.

Just to write. If I were an athlete, I'd go for a run. But I'm a writer. So I must write. Even if it's only for 15 minutes. Even if what I've written makes little sense.

To make sure that not everything I'm thinking is going out the window.

To remember.

And reflect.

And rant.

"Sometimes, though not that often, I wish I were still a writer, since so much goes through anybody's mind and right out the window, whereas, for a writer--even a shitty writer--so much less is lost."I just finished reading Larry's Party by Carol Shields, and realized as I read about the fictional Larry Weller going into a coma in his early forties just how frightened I am these days. My days are assignment-sized (presentations, papers, and class participation), my hours are lecture-sized, my minutes as long as a page, and my seconds do not so much as tick by as get tapped out on a keyboard.

I was standing in London Drugs today, waiting in line while an old lady dug out her change. A fierce-eyed man behind me muttered about "saving money while you hold up the goddamn line." I imagined replying, "being an asshole for the sake of saving 20 seconds is a far better thing." And then I had a flashback to standing in the aisle of the general store in Fox Creek, which in its entirety was no bigger than the length and width of the checkout area I was standing in.

I remembered being only a year or two older than Gunnar, and standing in that store: looking at the toy section, filled with the sort of nickel and dime junk you find in small town general stores. I recall it being a wonderful place though. I bought Star Wars trading cards there. Comic books. A plastic gorilla who I was convinced was King Kong. A G.I. Joe, the kind that was taller than Barbie, the kind with the kung-fu-grip.

And suddenly, I wanted to be home. I wanted to be where my son is. I want time to move differently. I don't want to be turning 38.

I'm finding it hard to age gracefully, it would seem.

So reading a book about a man in his mid-forties having a coma seems like a cruel and unusual punishment to inflict on oneself. But, like my time, I have no choice in the matter. It's required reading for my Canadian Women's Fiction class. And I need that class to get through my coursework. And I need that coursework to get my PhD.

And somehow, I'm convinced I need that PhD. to get beyond my past. My resume reads, "Only ever really done church work or retail." Which is effectively the most useless resume one can possess. I heard the inside scoop from an HR manager who told me that former pastors are about as unpopular a potential hire as one can find, outside ex-cons.

Yet every day, I ask myself if it is worth the effort. Every day, I wonder if the price is too high. And every day, I am reminded of Winston Churchill saying "if you are going through hell, keep going." Or as Trent Reznor put it, "The Way Out is Through."

Thankfully, Larry's Party doesn't end with the coma. And its central metaphor is the hedge maze, or labyrinth, which is described in the book as "a complex path." If ever I identified with a metaphor, it's this one, at this time.

So why blog? It's 10:53 on Tuesday night and I have another novel to read before class tomorrow. And half of D.H. Lawrence's The Rainbow for Thursday night. Another presentation due next week, along with a short paper on a presentation I did last week.

I blog because my chest hurts. I blog because I find myself occasionally short of breath. I blog to remind myself of the things I'm doing this for. I blog to remember how to write with fucking citations, or pedantic obscurancy, or proper punctuation or grammar.

Just to write. If I were an athlete, I'd go for a run. But I'm a writer. So I must write. Even if it's only for 15 minutes. Even if what I've written makes little sense.

To make sure that not everything I'm thinking is going out the window.

To remember.

And reflect.

And rant.

Monday, January 19, 2009

Updating the world of Gotthammer

You'll notice things look different around here. The blog has a new look, the website is virtually gone, and I have a new profile photograph.

All of this is to reflect my current space in life. As I move forward into my academic career, I need my online presence to reflect what I'm doing. Gotthammer began as a place to express myself, and currently, my expressions are all academic, and largely related to steampunk. So for the time being, the main site will become a hub for the blogs, as well as acting as an online curriculum vitae. My hope is that online c.v. will be a little more interesting than just a PDF document. But time will tell. I am incredibly busy these days: teaching full time between three campuses: The King's University College, Grant MacEwan, and Taylor University College; attending to my own graduate studies at the University of Alberta in Comparative Literature; working on papers and articles and presentations in preparation of my dissertation on Steampunk; and being a husband and a father. While I want to keep updating all the blogs, I will be focusing on the Steampunk Scholar, which is my latest blog - think of it as an online annotated bibliography.

I'll still post here from time to time. And once my course work is done, I can see getting back to Magik Beans. But I have a mission. As the new blog puts it, a "5 year mission." Feel free to come and journey with me some more. I appreciate everyone who's supported me here online over the years. I'm not going away. But I wanted to apprise you of the changes.

Now, if you'll excuse me, I have some Jane Austen to be reading.

All of this is to reflect my current space in life. As I move forward into my academic career, I need my online presence to reflect what I'm doing. Gotthammer began as a place to express myself, and currently, my expressions are all academic, and largely related to steampunk. So for the time being, the main site will become a hub for the blogs, as well as acting as an online curriculum vitae. My hope is that online c.v. will be a little more interesting than just a PDF document. But time will tell. I am incredibly busy these days: teaching full time between three campuses: The King's University College, Grant MacEwan, and Taylor University College; attending to my own graduate studies at the University of Alberta in Comparative Literature; working on papers and articles and presentations in preparation of my dissertation on Steampunk; and being a husband and a father. While I want to keep updating all the blogs, I will be focusing on the Steampunk Scholar, which is my latest blog - think of it as an online annotated bibliography.

I'll still post here from time to time. And once my course work is done, I can see getting back to Magik Beans. But I have a mission. As the new blog puts it, a "5 year mission." Feel free to come and journey with me some more. I appreciate everyone who's supported me here online over the years. I'm not going away. But I wanted to apprise you of the changes.

Now, if you'll excuse me, I have some Jane Austen to be reading.

Monday, January 12, 2009

Movies to see in 2009

In theaters:

The Watchmen

9

Star Trek

2012

El Camino

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

Coraline

Fanboys

Terminator: Salvation

To wait for DVD

Inkheart

Transformers 2

X-Men Origins: Wolverine

Leftovers from 2008 yet to see...

Australia

Quantum of Solace

Burn After Reading

Valkyrie

Madagascar 2

Tale of Despereaux

The Watchmen

9

Star Trek

2012

El Camino

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

Coraline

Fanboys

Terminator: Salvation

To wait for DVD

Inkheart

Transformers 2

X-Men Origins: Wolverine

Leftovers from 2008 yet to see...

Australia

Quantum of Solace

Burn After Reading

Valkyrie

Madagascar 2

Tale of Despereaux

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)